Go north from Rome. Outside the city, vast fields of flax blanket the hills. Now, in late summer, their blue flowers unfurl, reeling in the wind like ocean waves. From the small-town tavern where you spent the night, the walk further afield takes an hour or two. As evening approaches, the air softens and releases you from its embrace. At the crest of a hill, the via narrows. A labyrinth of overgrown trees seems to part on your ascent, an invitation past the iron gates that lie ahead. Beyond, the light is transparent, cast through foliage in trembling amber greens. Herbs grow wild and unkempt, a dense tangle of thyme, lavender and lemon balm suspended in the heady air.

The garden is hypnotic — it beckons you to explore. A veil of twilight obscures the sun and long shadows brush their fingers across the ground, painting the leaves in darkness. At the witching hour, an apparition appears — whether a vision of faery lights or a memory briefly resurrected, it leaves as quickly as it arrives.

Dim figures quiver on the hedges, shapes you can barely perceive. With each flicker of the eye, they shift out of sight. You are unsure what you’ve discovered here – this place feels at once elusive and familiar.

Weeks of travel have taken you through the countryside, where you’ve lingered briefly in a string of small towns. They all blur together into a month-long memory – a repetition of cobbled streets, crumbling ramparts and cypress trees. In every village there is an abbey where the monks’ evening chants rise above stone walls like a beacon in the night, vespers sung as the sun sinks below the horizon, turning the sky to dusk.

The darker it gets, the less you feel that you are alone. As the black sky revives its first stars, a single candle illuminates a window of the castello beyond the garden. You look up and count the constellations, trying to identify each as a touchstone: Cassiopeia…Hercules… Camelopardalis and his forgotten companion Tarandus. The stories of the past are written above, the sky an archive of ancient myths.

You look back at the castello. Inside, a silhouette moves in tandem with a candle, passing by window after window until it turns down a hall and the light is extinguished. You gather your wits, walk swiftly towards the door, knock and wait.

IL CASTELLO

A cold moment passes and a man answers the door. His hair is dark, his eyes dim. He wears a waxed wool suit, the type that fell out of fashion decades ago, yet it retains the crisp seams of a garment well cared for. “Are you here to see the painting?” he asks. You search for an answer, but a fog clouds your mind. “Yes,” you answer, not knowing why.

He waves his hand and walks, signaling you to follow him through a steep stairwell. “I have tried to light the candles,” he says, “yet they’re always extinguished. There are hundreds of them lining the halls. On the feast day of San Giacomo, it is my task to light a vigil for saints and lost souls, but they flicker a moment, then go out.” He pauses. “Old castles are always so drafty.”

You pass by faded frescoes on the walls. The murals seem to sway in the wavering candlelight. “The shadows are not as benign as they seem,” he warns. “This castle has swallowed people whole. There have been disappearances.” He speaks so plainly, you wonder if he’s teasing you. His tone is difficult to decipher, his face turned away, his heels tapping the stone floor in a fast clip as you struggle to keep up. He stops, and you’re suddenly aware that you’ve followed him into a room cluttered with shrouded canvases.

In the center of the room is a table, where traces of pigments mixed with dust line the rim of a mortar and pestle. “Here you are,” says the man, unveiling a portrait of an older woman. The brushstrokes on her skin have been erased and repainted many times, making her appear hesitant, as if she is not quite ready to come into being. “We are still trying to understand,” he says, “who she is. Your expertise is much appreciated.”

Your eyes drift to a nearby desk with a yellowed book, opened to pages of celestial drawings. You sink into the desk chair, running your fingers along the dried leaves of the book and skimming its words. They are as impenetrable as ancient runes. “It is the book of time,” says the man. As he speaks, the words seem to lift themselves from the page, forming a string of pictures in your mind. “If we understood the language of the stars,” he says, his voice growing distant, “we would long ago have learned where to look for the things that are lost.”

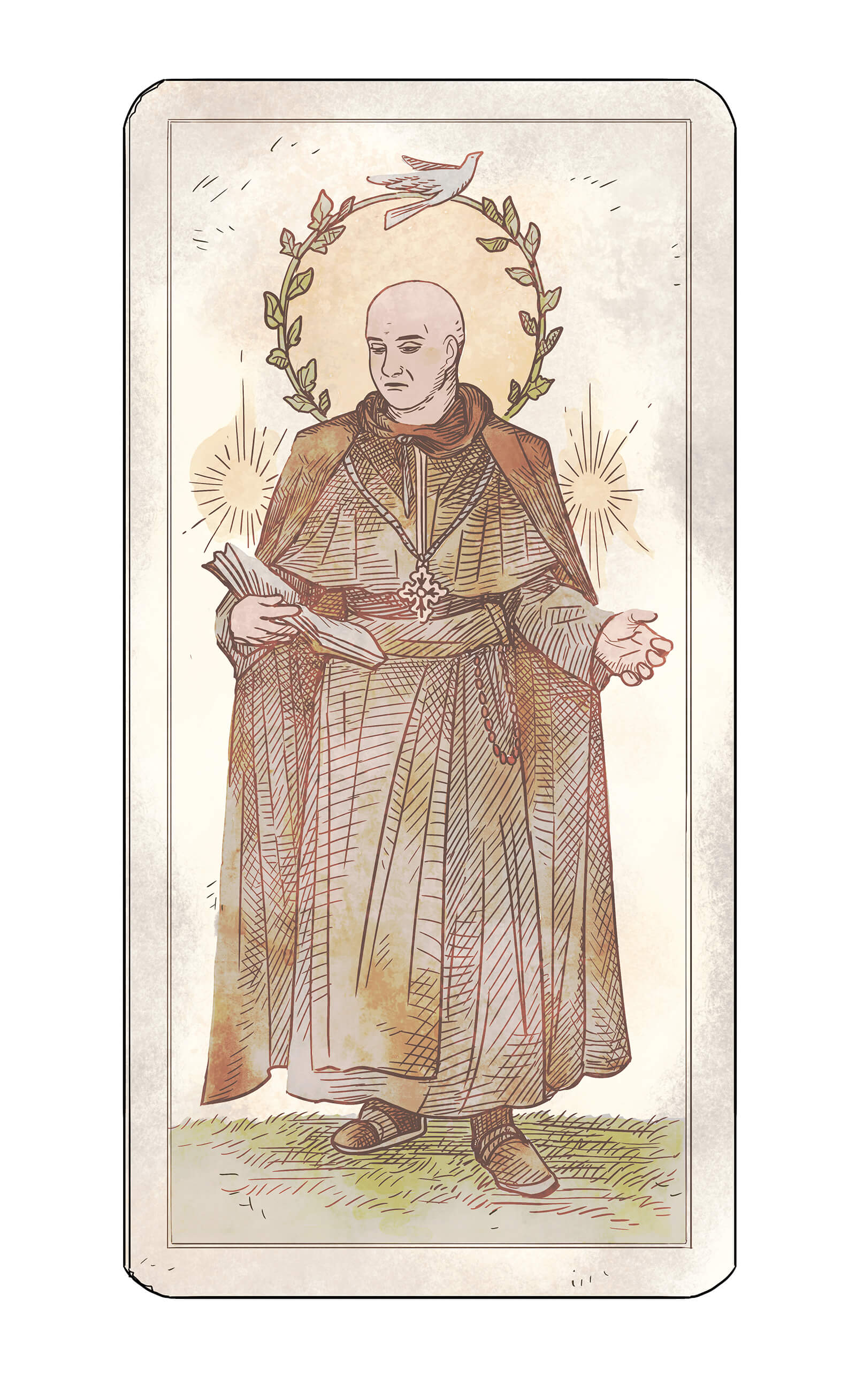

IL VESPRO

In the dark sky, a bright star shines above a monastery. There lived a monk, whose job it was to transcribe prayers into the Book of Hours. Every day, he greeted the dawn with morning prayers, and every evening he attended Vespers just before the sun sank below the horizon. His day was divided into eight parts, each marked by prayers, which he dutifully copied with his quill onto goatskin parchment.

One day, the abbot brought him a new book to copy. “Time is a vast house,” the abbot told him. “It contains many treasures, some precious and some misplaced for good reason. Tread carefully.” Bound in stiff leather, the book’s cover was cracked and stamped with just three letters, each lined in flaking gold leaf: ARA. It was not a prayer book, but something older, from the time before one God swallowed the sorcerers of the old world.

As the monk transcribed each line, a dark, moss-covered forest came into his mind. There, half-human creatures rose from the flanks of horses. The centaurs followed old ways and made sacrifices to appease the gods. They were violent, but one was peaceful. He studied the stars and taught travelers to see the maps hidden within them. Over time, he became a great teacher and guide.

One day, walking through the woods, the centaur encountered a wolf, snarling to reveal enflamed gums. The wolf lunged at the centaur, who impaled him on his spear. As the beast bled out, the centaur looked down and saw his own knee wounded, leaking a steady, dark red stream. The centaur summoned his energy and limped through the woods, leaving a river in his wake. At the edge of the wood, he died. The wind carried the news of his death to the gods, who lifted his body from the ground and set it in the sky. In the heavens still, Centaurus spears the wolf Lupus on the holy altar of Ara. The smoke that rises from that sacrificial constellation forms the Milky Way.

The monk was so consumed by the story that he continued to work as evening fell, lighting a candle to see his parchment. Vespers came and went, and he did not appear. The abbot went to the scriptorium to look for his missing monk, but the damp stone room was empty. The monk did not appear at morning prayers the next day, or the next.

Eight days later, when the brothers were gathered at Vespers, they saw a monk appear above them in the air. His robes became entangled in the altar rails, and he struggled to free himself. “If we do not help him,” said the abbot, “he will be forever trapped between our worlds.” They gathered his robes, which turned to smoke in their hands as the monk drifted away from the altar and returned to the sky.

IL VESPRO

In the dark sky, a bright star shines above a monastery. There lived a monk, whose job it was to transcribe prayers into the Book of Hours. Every day, he greeted the dawn with morning prayers, and every evening he attended Vespers just before the sun sank below the horizon. His day was divided into eight parts, each marked by prayers, which he dutifully copied with his quill onto goatskin parchment.

One day, the abbot brought him a new book to copy. “Time is a vast house,” the abbot told him. “It contains many treasures, some precious and some misplaced for good reason. Tread carefully.” Bound in stiff leather, the book’s cover was cracked and stamped with just three letters, each lined in flaking gold leaf: ARA. It was not a prayer book, but something older, from the time before one God swallowed the sorcerers of the old world.

As the monk transcribed each line, a dark, moss-covered forest came into his mind. There, half-human creatures rose from the flanks of horses. The centaurs followed old ways and made sacrifices to appease the gods. They were violent, but one was peaceful. He studied the stars and taught travelers to see the maps hidden within them. Over time, he became a great teacher and guide.

One day, walking through the woods, the centaur encountered a wolf, snarling to reveal enflamed gums. The wolf lunged at the centaur, who impaled him on his spear. As the beast bled out, the centaur looked down and saw his own knee wounded, leaking a steady, dark red stream. The centaur summoned his energy and limped through the woods, leaving a river in his wake. At the edge of the wood, he died. The wind carried the news of his death to the gods, who lifted his body from the ground and set it in the sky. In the heavens still, Centaurus spears the wolf Lupus on the holy altar of Ara. The smoke that rises from that sacrificial constellation forms the Milky Way.

The monk was so consumed by the story that he continued to work as evening fell, lighting a candle to see his parchment. Vespers came and went, and he did not appear. The abbot went to the scriptorium to look for his missing monk, but the damp stone room was empty. The monk did not appear at morning prayers the next day, or the next.

Eight days later, when the brothers were gathered at Vespers, they saw a monk appear above them in the air. His robes became entangled in the altar rails, and he struggled to free himself. “If we do not help him,” said the abbot, “he will be forever trapped between our worlds.” They gathered his robes, which turned to smoke in their hands as the monk drifted away from the altar and returned to the sky.

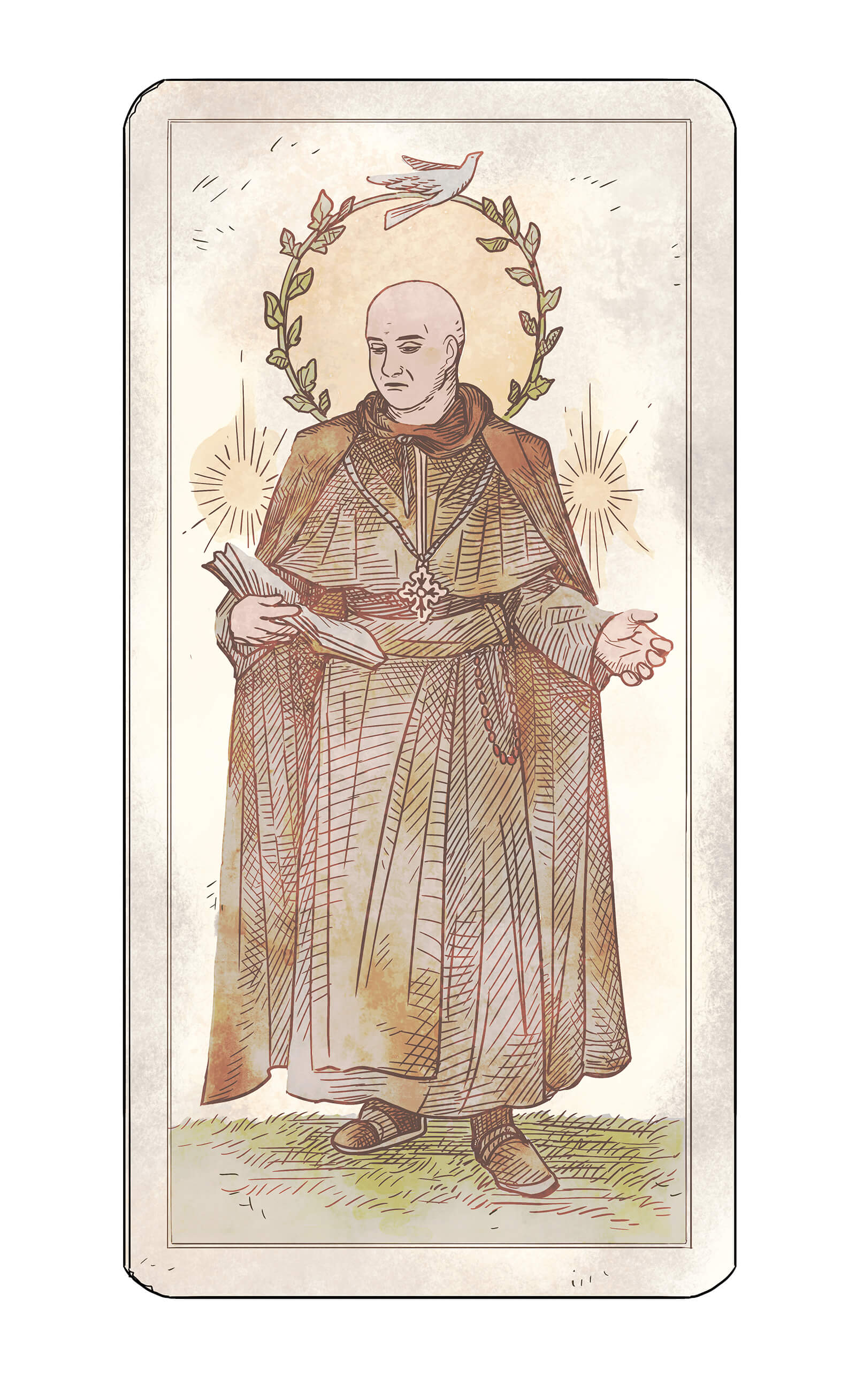

IL DOTTORE

In the time of the Black Death, there was a doctor who traveled through Italy. In every city the plague greeted him. The people recognized his uniform: the waxed wool cloak and bird-like mask, its beak stuffed with guardian herbs — camphor, mint, cloves and myrrh.

Around his waist, he carried tools to treat the sick — sponges soaked in a tincture of vinegar and herbs. He cared for those suffering but never succumbed to their fate.

Rumors followed the doctor wherever he traveled. Unlike the others, he did not flee or die. How did he preserve himself? Was he a magician? A demon? As he made his way north, the rumors grew thick, poisonous vines extending their tendrils from town to town. In Siena, he failed to save a Cardinal, and charges of heresy soon followed from Rome.

To avoid arrest, he left Siena in the darkness of night and sought refuge in a country villa, abandoned by a noble family fleeing the plague. He dashed from room to room with ember-tipped mugwort in hand, waving it to cleanse the house. As the air filled with a dark green scent, the smoke swept over the floor and out the doorways. Only after the harmful spirits had gone did he pull his treasure from his pouch.

A plump little body with a brown rind emerged. Stringy roots formed its fingers and toes, and green leaves grew from the crown of its head. It rubbed its soil-encrusted eyes and wiped the dirt from its nose. As the mandrake slowly woke from sleep, the doctor filled his own ears with cotton. A mandrake’s cry can induce a coma — its shriek can be fatal.

As the mandrake looked around the villa, he did not cry, but began to sing. With each note, the house yawned and creaked, waking from its long sleep. The shutters opened, and sunlight streamed in. The rugs shook the dust from their weaves. Color returned to the pale, faded walls. When the house was clean and warm, the mandrake rested. Spent from singing, he crawled back into the pouch to sleep until awoken again.

“This house has been restored many times.” You are back in the room of shrouded paintings, sitting at your desk, a book open before you. The man in the wool suit sits across from you, his hands resting on his knees. “That book,” he says, “is from a very old collection — one that predates the home’s current owners.”

“Who are the current owners?” you ask. “And what happened to the doctor?” The man in the wool suit stands, closes your book, and picks it up from the table. “He hid until the plague subsided and the charges against him were forgotten.” The man pauses to return the book to a shelf, where he places it next to an elaborate inlaid wood box. “No one knows what became of the mandrake,” he grins. “As for the current owner, I am happy to take you to the lady who lives here.”

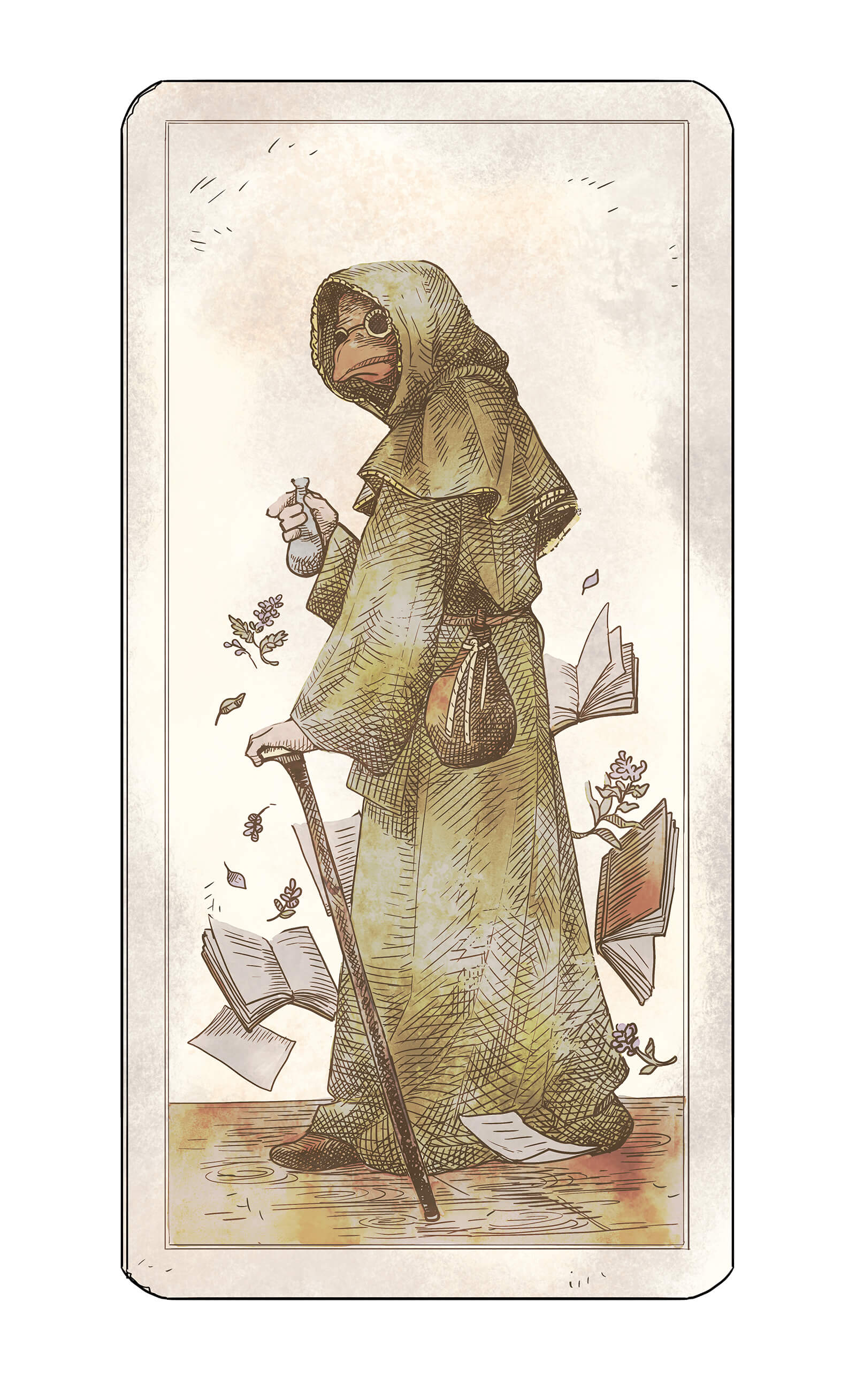

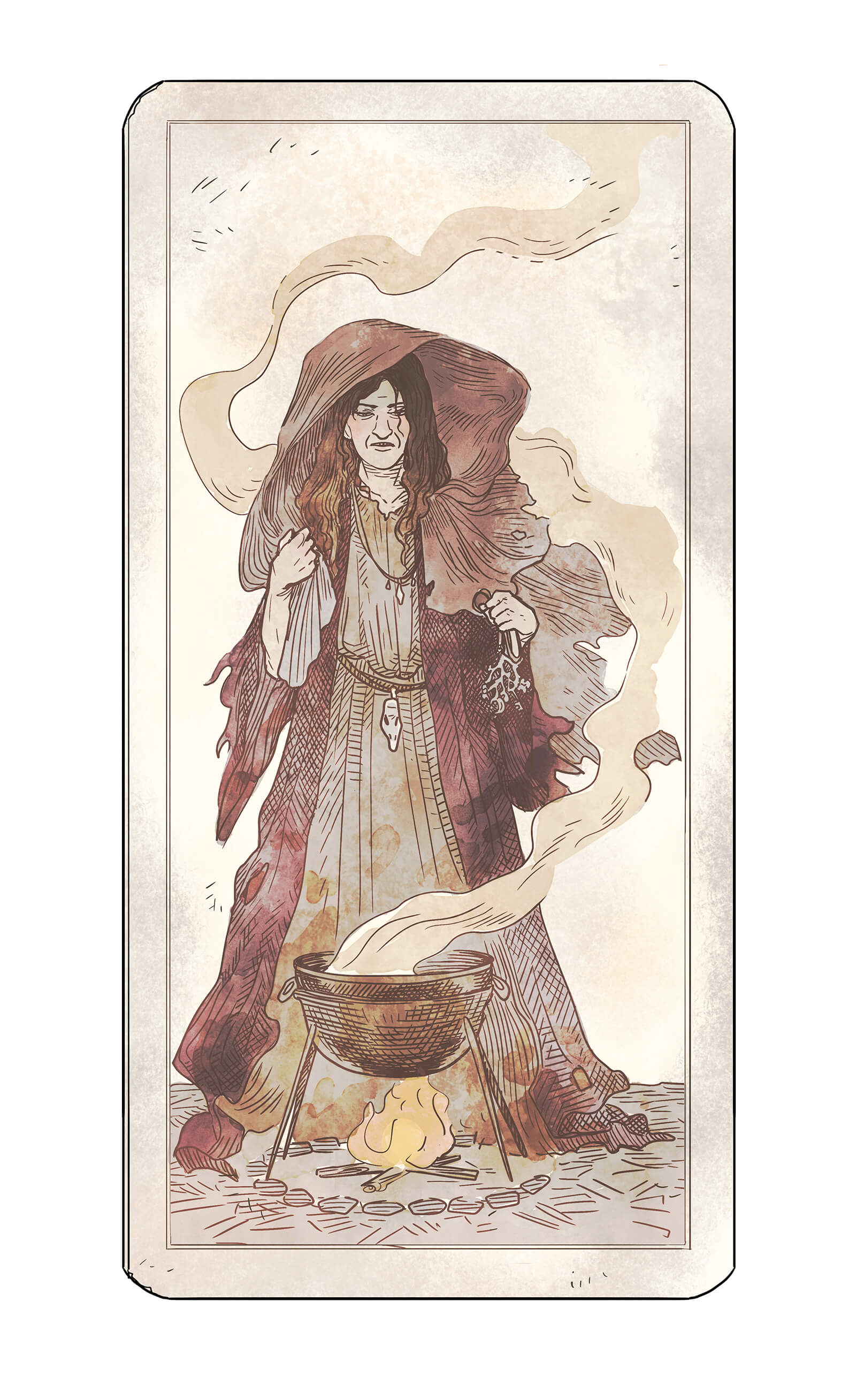

LA STREGA

Following the man in the wool suit, you emerge from your room to find that the light has changed. The halls are gilded now with hazy shafts of sun. Is it dawn or dusk? Have you spent the night reading? As you follow him through the halls, the light grows stronger. Encrusted in thick layers of peeling lime plaster, the mortared cracks in the castle walls catch the sun as if gold dust had been used to fill them.

He leads you to an ancient, crumbling kitchen. Vines strangle the hearth and the smell of damp earth leaches through the cobbled stone floors. Near the hearth sits a crooked figure. She is very old, with few front teeth left. Deep grooves line her face, and her hands shake slightly in her lap. She raises one of them, knuckles gnarled and knotted like tree roots, to summon you.

As you approach, you’re overtaken by the musty, bitter scent of rue. “The earth knows you,” she says, in a rattling voice. “Even when you have lost yourself.” Quaking as she rises from her chair, she turns to the archaic wood stove, where an iron kettle awaits her. Steam rises, a mist that shrouds the rust. She pours the kettle’s contents into a chipped clay cup and passes it to you.

You look for your guide, but he is gone. You are alone with the old woman. The cup warms your hands as cold air wafts through an opening in the castle wall, more a hole than a window. Inside your cup, dried leaves float in amber liquid. “I know what you want,” the old woman says, sinking back into her chair. “Drink this, and it will lead you there.” You wonder how this old woman could know your thoughts when they’ve wholly evaded you. For months you’ve been traveling aimlessly, removing yourself from the world in the hope that you might finally grasp it. On the point of forgetting everything, you are suddenly compelled to remember it all. The sound of a straw broom on stone, the bright scent of laundry drying on the line.

“When the plants come to you, listen,” says the old woman. “They will bring you home.” You look up, and she is changed — not younger, exactly, but ageless. The steam from the kettle surrounds her, like a veil. You drink. The tea is bitter, strong and brackish — it tastes of herbs and dirt, and grit lingers on your tongue. After a few moments, you feel yourself drop, yet the stone-cobbled floor is still there. On the air, a perfume arrives — smoky, laden with vermillion petals, and tasting of sleep.

LA STREGA

Following the man in the wool suit, you emerge from your room to find that the light has changed. The halls are gilded now with hazy shafts of sun. Is it dawn or dusk? Have you spent the night reading? As you follow him through the halls, the light grows stronger. Encrusted in thick layers of peeling lime plaster, the mortared cracks in the castle walls catch the sun as if gold dust had been used to fill them.

He leads you to an ancient, crumbling kitchen. Vines strangle the hearth and the smell of damp earth leaches through the cobbled stone floors. Near the hearth sits a crooked figure. She is very old, with few front teeth left. Deep grooves line her face, and her hands shake slightly in her lap. She raises one of them, knuckles gnarled and knotted like tree roots, to summon you.

As you approach, you’re overtaken by the musty, bitter scent of rue. “The earth knows you,” she says, in a rattling voice. “Even when you have lost yourself.” Quaking as she rises from her chair, she turns to the archaic wood stove, where an iron kettle awaits her. Steam rises, a mist that shrouds the rust. She pours the kettle’s contents into a chipped clay cup and passes it to you.

You look for your guide, but he is gone. You are alone with the old woman. The cup warms your hands as cold air wafts through an opening in the castle wall, more a hole than a window. Inside your cup, dried leaves float in amber liquid. “I know what you want,” the old woman says, sinking back into her chair. “Drink this, and it will lead you there.” You wonder how this old woman could know your thoughts when they’ve wholly evaded you. For months you’ve been traveling aimlessly, removing yourself from the world in the hope that you might finally grasp it. On the point of forgetting everything, you are suddenly compelled to remember it all. The sound of a straw broom on stone, the bright scent of laundry drying on the line.

“When the plants come to you, listen,” says the old woman. “They will bring you home.” You look up, and she is changed — not younger, exactly, but ageless. The steam from the kettle surrounds her, like a veil. You drink. The tea is bitter, strong and brackish — it tastes of herbs and dirt, and grit lingers on your tongue. After a few moments, you feel yourself drop, yet the stone-cobbled floor is still there. On the air, a perfume arrives — smoky, laden with vermillion petals, and tasting of sleep.

IL PAPAVERO

In poppy fields the mist hangs low.

From the forest calls a crow.

Below, the dark ground opens up.

Tree roots hold the black earth, cupped.

Where the sacred well springs forth

A silt-laced aquifer flows north.

From underfoot it beckons, follow

Over stone and round the hollow.

A tangled net of thin roots dance

Above ground, poppies sway in trance.

They lift red faces to the sun

That rules their sleepy life, half-done.

Returning water to the ground

Their leaves and stems are homeward-bound.

The silent earth does not discern.

It welcomes all; we all return.

In sleep our unlived lives play out.

From dreams, the seed of longing sprouts.

To know the secrets of the earth

And sow them for our own rebirth.

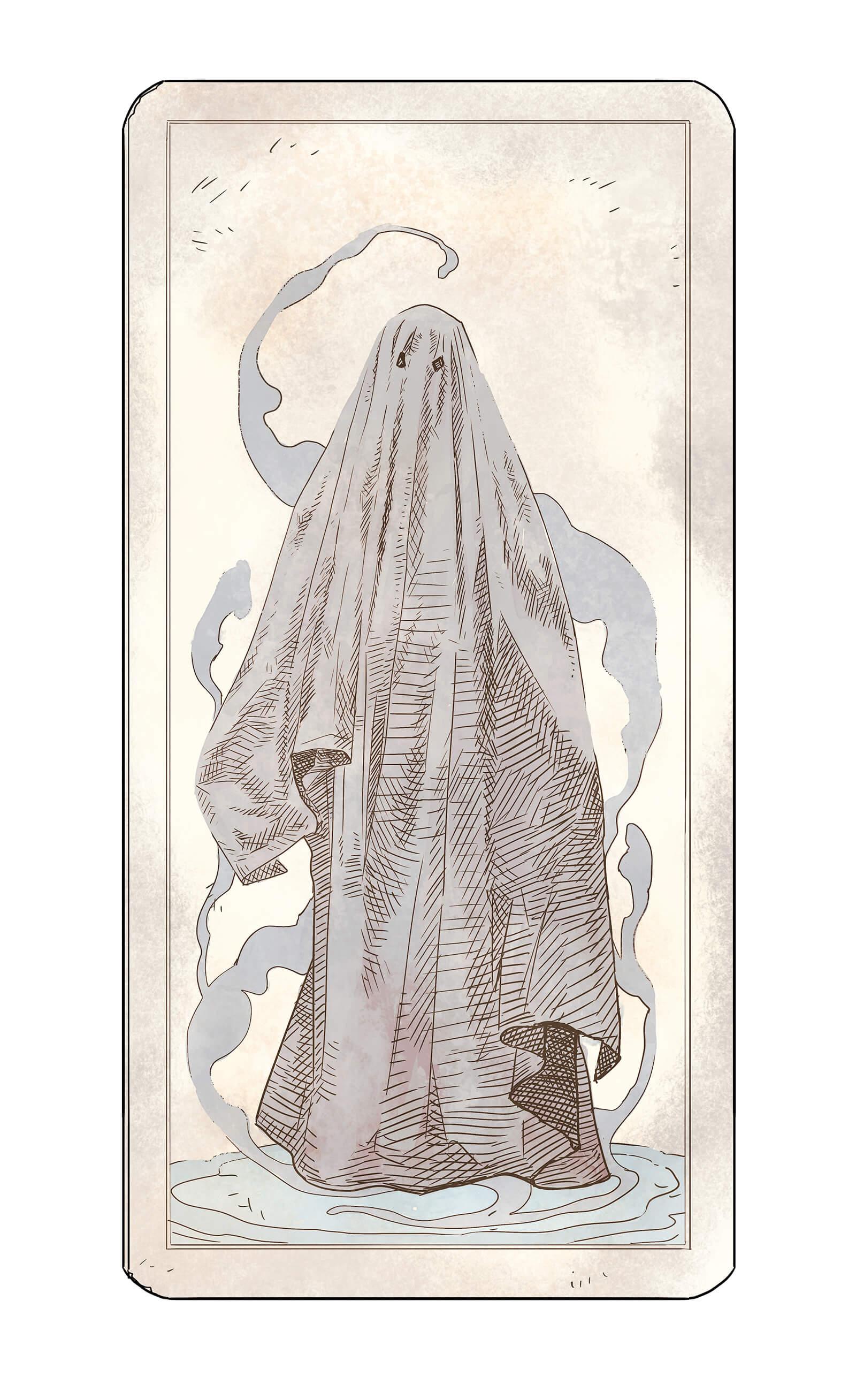

LO SPETTRO

The dim kingdom awaits. A gaping entrance to the earth, large enough to stoop and walk through, implores you to come in. Like Dante scrambling across shattered rocks down the ravine to the underworld, you comply. The only way out is through.

Ahead, murky paintings hang on a plastered wall. You are back inside the house. As you approach the entrance hall, a mournful hum reaches your ears. “Who is there?” you ask. Silence responds, followed by a faint and faraway greeting. “Hello.” The voice that answers is hollow but clear.

A sheet steps forward from the shadows, with two holes cut for eyes, like a child playing dress-up. It speaks softly, gently. “I live here,” it says. As the sheet speaks, it sways in the air. “Can I tell you a story?” You nod.

“My friend lived here. On dark nights, we played in the garden. She covered a lantern with a piece of cloth then hid behind the hedges. When she was ready for me to find her, she uncovered her lantern and I followed the light. As I drew near, she cloaked the lantern and ran again. Another direction, another flash of lantern light, until finally I caught her.” The words break off, then continue between quiet pauses.

“Then, she became suddenly ill. I stayed up with her at night when she couldn’t sleep from coughing. She passed within a week.” As you listen, many questions fill your head, but you hold them to yourself.

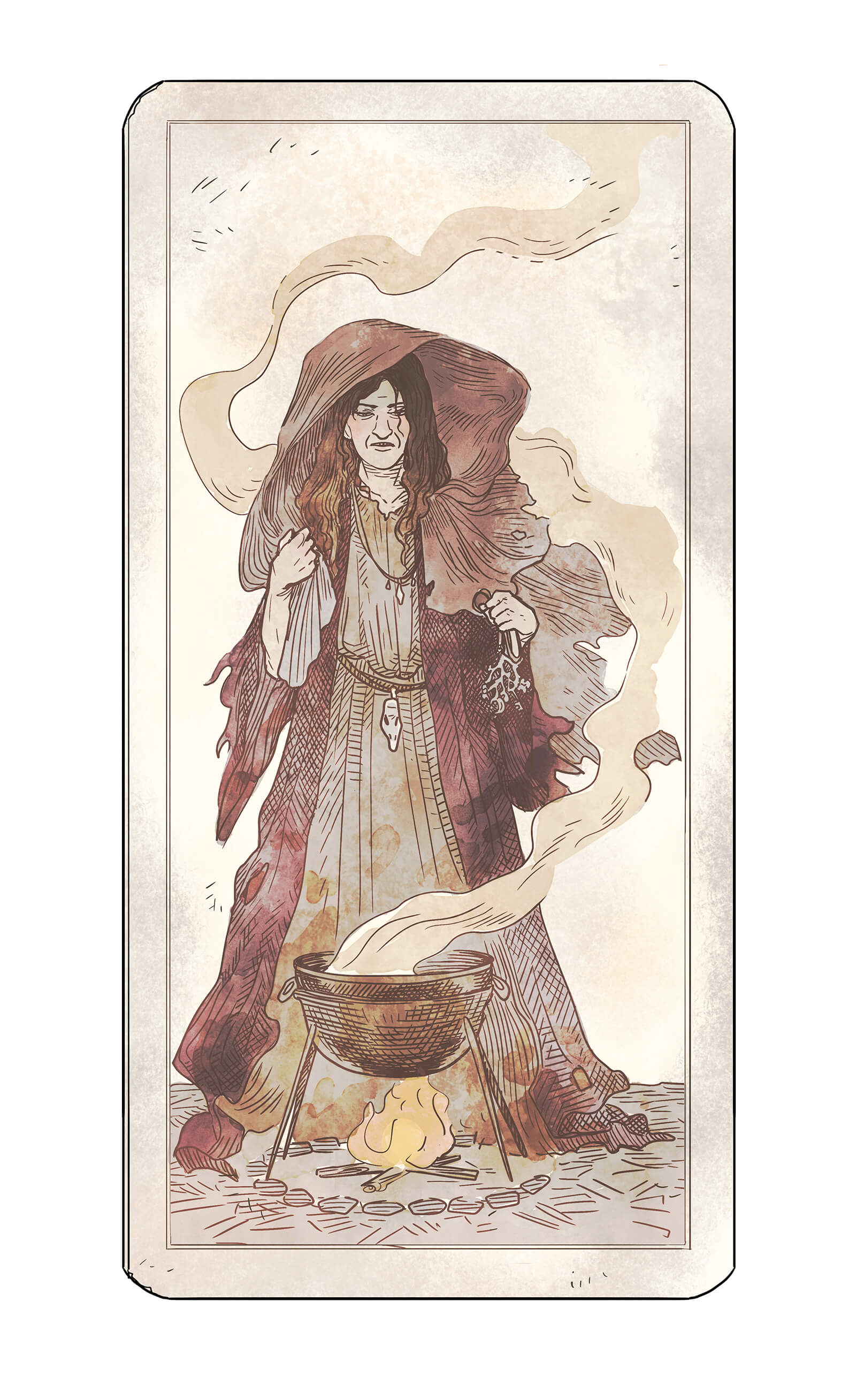

“There was a woman who worked in the kitchens. A witch. She saw my sadness and offered to lift the veil between this world and the next, so that I might find my friend once more.” The sheet stutters and sways. “She gave me a tea to drink, and she told me I would meet my friend on a bridge. We could see and speak to one another, but I could not follow.”

A slight breeze lifts the sheet gently from the floor, revealing nothing — not even a shadow — underneath. It continues, “I drank the tea and fell into a heavy sleep. When I awoke, my friend stood before me. I said hello, and so did she. Then she turned to cross the bridge. I followed her until a bright light blocked my path. It swelled and swallowed her. Then I was left alone in this dark house.”

“Are you a ghost?” You ask the obvious. The sheet sways, in a movement that mimics a nod. “There are many of us here,” it says. “In the garden, by the road. We appear in different forms.”

At these words, a blue flame appears, like the wisp of a candle. Then another, and another, until the hall is filled with floating lights. “This is my favorite game,” says the sheet. “Let’s follow them.”

LO SPETTRO

The dim kingdom awaits. A gaping entrance to the earth, large enough to stoop and walk through, implores you to come in. Like Dante scrambling across shattered rocks down the ravine to the underworld, you comply. The only way out is through.

Ahead, murky paintings hang on a plastered wall. You are back inside the house. As you approach the entrance hall, a mournful hum reaches your ears. “Who is there?” you ask. Silence responds, followed by a faint and faraway greeting. “Hello.” The voice that answers is hollow but clear.

A sheet steps forward from the shadows, with two holes cut for eyes, like a child playing dress-up. It speaks softly, gently. “I live here,” it says. As the sheet speaks, it sways in the air. “Can I tell you a story?” You nod.

“My friend lived here. On dark nights, we played in the garde

n. She covered a lantern with a piece of cloth then hid behind the hedges. When she was ready for me to find her, she uncovered her lantern and I followed the light. As I drew near, she cloaked the lantern and ran again. Another direction, another flash of lantern light, until finally I caught her.” The words break off, then continue between quiet pauses.

“Then, she became suddenly ill. I stayed up with her at night when she couldn’t sleep from coughing. She passed within a week.” As you listen, many questions fill your head, but you hold them to yourself.

“There was a woman who worked in the kitchens. A witch. She saw my sadness and offered to lift the veil between this world and the next, so that I might find my friend once more.” The sheet stutters and sways. “She gave me a tea to drink, and she told me I would meet my friend on a bridge. We could see and speak to one another, but I could not follow.”

A slight breeze lifts the sheet gently from the floor, revealing nothing — not even a shadow — underneath. It continues, “I drank the tea and fell into a heavy sleep. When I awoke, my friend stood before me. I said hello, and so did she. Then she turned to cross the bridge. I followed her until a bright light blocked my path. It swelled and swallowed her. Then I was left alone in this dark house.”

“Are you a ghost?” You ask the obvious. The sheet sways, in a movement that mimics a nod. “There are many of us here,” it says. “In the garden, by the road. We appear in different forms.”

At these words, a blue flame appears, like the wisp of a candle. Then another, and another, until the hall is filled with floating lights. “This is my favorite game,” says the sheet. “Let’s follow them.”

LA CANDELA

Like fireflies, the lights disperse to wander through the halls. They float in lazy clusters, stringing themselves together only to scatter the next second. You follow one a few steps forward until it’s gone. Another appears and leads you astray, then another. After drifting for a while, you come upon the door to a library. You enter a study lined with bookshelves and, as quickly as it arrived, the ghost is gone.

In this room, a rich silence shuts out the rest of the world, like a heavy embroidered curtain drawn over the door. The shelves are laden with leather books, some stamped with gold-leaf peacock feathers or gilded medallions. Their titles conjure stories from long ago: The Man Wreathed in Seaweed, The Tempest, The Odyssey. You choose one, bound in blue leather and embellished with bronze leaves. At the edge of the room is a chaise. You sit, lean back and let the book fall open where it wants. “There is a time for many words,” you read, “and there is also a time for sleep.”

Your reverie is broken by a knock at the window, a windblown tree branch lashing at the pane. The curtains lift their hems, like whirling dervishes in trance, and the candles sputter. For a moment, the study seems to darken. In the gloom, the gilded spines of books glow like quartz lining the walls of some ancient cave. You close your eyes to empty your mind of illusions.

On opening them, you’ve fallen deeper into fantasy. The candles all burn with blue flames as though each houses its own faery. Now the lights move back and forth, above and below, trailing lines of light between them, weaving a net around the room. A voice speaks from an unknown distance. “You have gathered the myths of centuries,” it says, “because you believe in none.”

In the midst of these visions, it takes great effort to rise from the chaise. A shrill wind enters the room and holds you back. Standing to walk to the door, you feel as if you’re being split in two. You make your way to the hall, where the wind suddenly ceases. Exhausted, you stumble through the first open door into a chamber furnished sparely with a bed and desk. Ancestral portraits hang on the walls. You collapse into the bed, and a feverish sleep overtakes you.

IL DIAVOLO

The devil comes to lost souls in dreams. In your dream you are a writer, drafting stories at your desk late into the night. Your clothes are threadbare, your nose red with cold. A candle burns beside you, keeping watch over lines of lonely prose. As rain taps the windowpane, your mind treads carefully through a melancholy forest, stepping over twisted roots and thick reeds. The sudden screech of an owl startles you, and you look up to find yourself – body and soul – in the woods.

On an old stump sits a man. He is as crooked and broken as a fallen tree. His skin is rough and pocked, bark-like, making it hard to tell where the stump ends and the man begins. “Who are you?” you ask. The man grins, his eyes flashing. “I am the devil,” he says, “and I have something for you.” The devil holds out a small bag sewn from striped cloth. “This will supply you with money for as long as you live,” he says. He stops to consider his words, then chooses the plainest ones available. “But it will cost you.”

With limitless money, you could buy a house and hire a servant. You would never want for food. Still, you hold back. Those who spin stories for a living know how a deal with the devil will end. “I’ll take it,” you say, “if you grant me one favor. Anything that comes into the bag is mine to keep.” The devil shrugs and passes you the bag. “What’s yours is yours,” he says.

For years, or maybe only a moment, you are happy in your dream. Your table and your house are never empty, yet a heavy sadness comes over you every night. Knowing the burden you carry in the bag, you resolve to give away twice what you take. With your money, you free others from their troubles.

After a lifetime, the devil pays a visit. Together, you walk to the underworld bridge. With each step, the voices of the damned grow nearer, until the wind shrieks with their calls. Here, you stop. “Devil,” you say. “Before we go any further, let me lay down my burden.” You take the striped bag from your coat. You leave your bag on the bridge and you walk on, reaching the threshold to the underworld. “I won’t go in,” you say. The devil laughs, and you draw yourself up to look him in the eye. “Years ago, you granted that anything inside the bag was mine. I gave away all I could, replacing each gift with a part of my soul. Now, it is safe in the bag.” The devil grins. “That may be,” he says, “but a safe soul is not a free soul. Hell cannot take you, but neither can heaven.” With that, you cross the bridge, evaporating into smoke. The bag burns, and the ember within it floats into the air, forever to drift on the wind.

IL DIAVOLO

The devil comes to lost souls in dreams. In your dream you are a writer, drafting stories at your desk late into the night. Your clothes are threadbare, your nose red with cold. A candle burns beside you, keeping watch over lines of lonely prose. As rain taps the windowpane, your mind treads carefully through a melancholy forest, stepping over twisted roots and thick reeds. The sudden screech of an owl startles you, and you look up to find yourself – body and soul – in the woods.

On an old stump sits a man. He is as crooked and broken as a fallen tree. His skin is rough and pocked, bark-like, making it hard to tell where the stump ends and the man begins. “Who are you?” you ask. The man grins, his eyes flashing. “I am the devil,” he says, “and I have something for you.” The devil holds out a small bag sewn from striped cloth. “This will supply you with money for as long as you live,” he says. He stops to consider his words, then chooses the plainest ones available. “But it will cost you.”

With limitless money, you could buy a house and hire a servant. You would never want for food. Still, you hold back. Those who spin stories for a living know how a deal with the devil will end. “I’ll take it,” you say, “if you grant me one favor. Anything that comes into the bag is mine to keep.” The devil shrugs and passes you the bag. “What’s yours is yours,” he says.

For years, or maybe only a moment, you are happy in your dream. Your table and your house are never empty, yet a heavy sadness comes over you every night. Knowing the burden you carry in the bag, you resolve to give away twice what you take. With your money, you free others from their troubles.

After a lifetime, the devil pays a visit. Together, you walk to the underworld bridge. With each step, the voices of the damned grow nearer, until the wind shrieks with their calls. Here, you stop. “Devil,” you say. “Before we go any further, let me lay down my burden.” You take the striped bag from your coat. You leave your bag on the bridge and you walk on, reaching the threshold to the underworld. “I won’t go in,” you say. The devil laughs, and you draw yourself up to look him in the eye. “Years ago, you granted that anything inside the bag was mine. I gave away all I could, replacing each gift with a part of my soul. Now, it is safe in the bag.” The devil grins. “That may be,” he says, “but a safe soul is not a free soul. Hell cannot take you, but neither can heaven.” With that, you cross the bridge, evaporating into smoke. The bag burns, and the ember within it floats into the air, forever to drift on the wind.

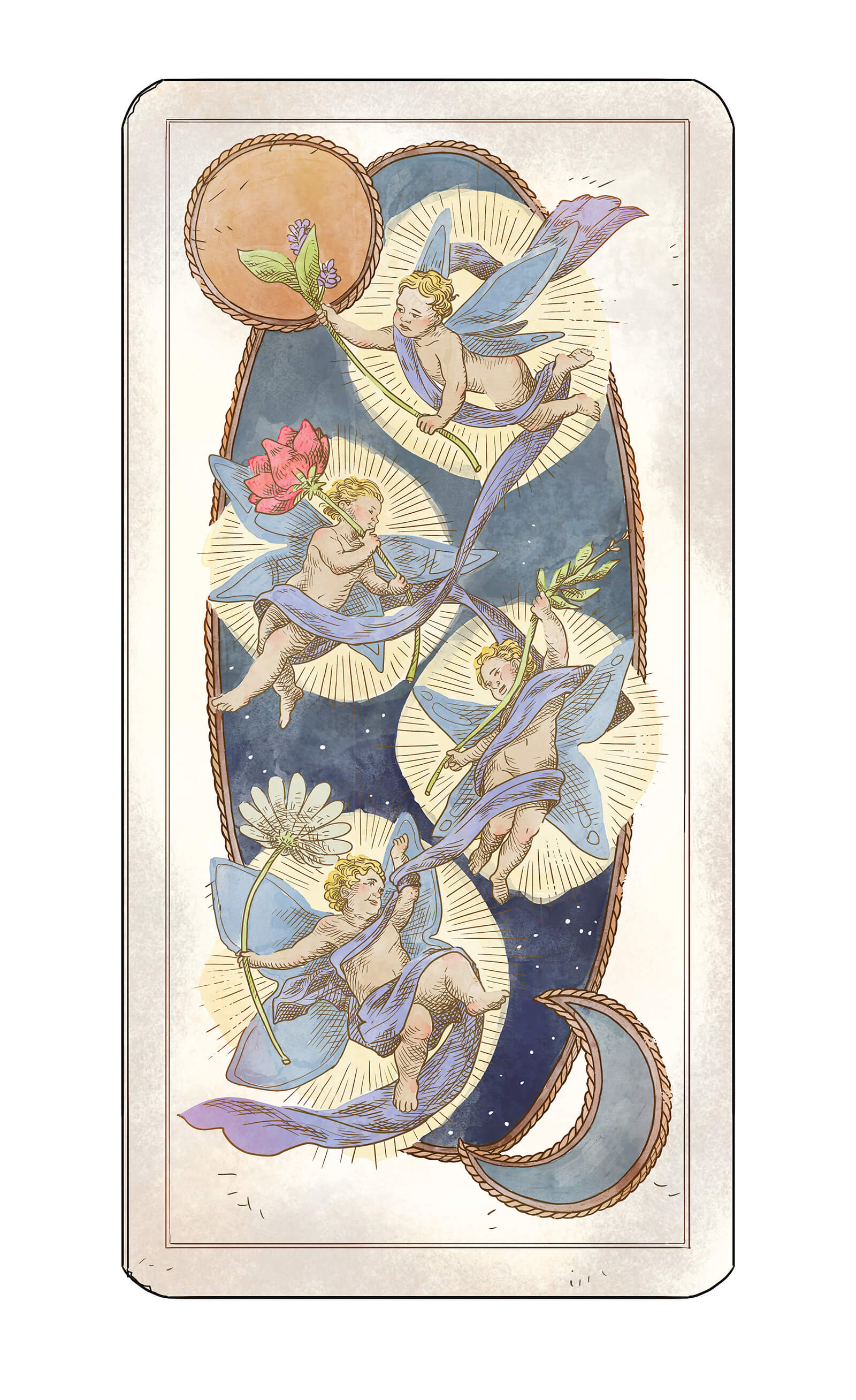

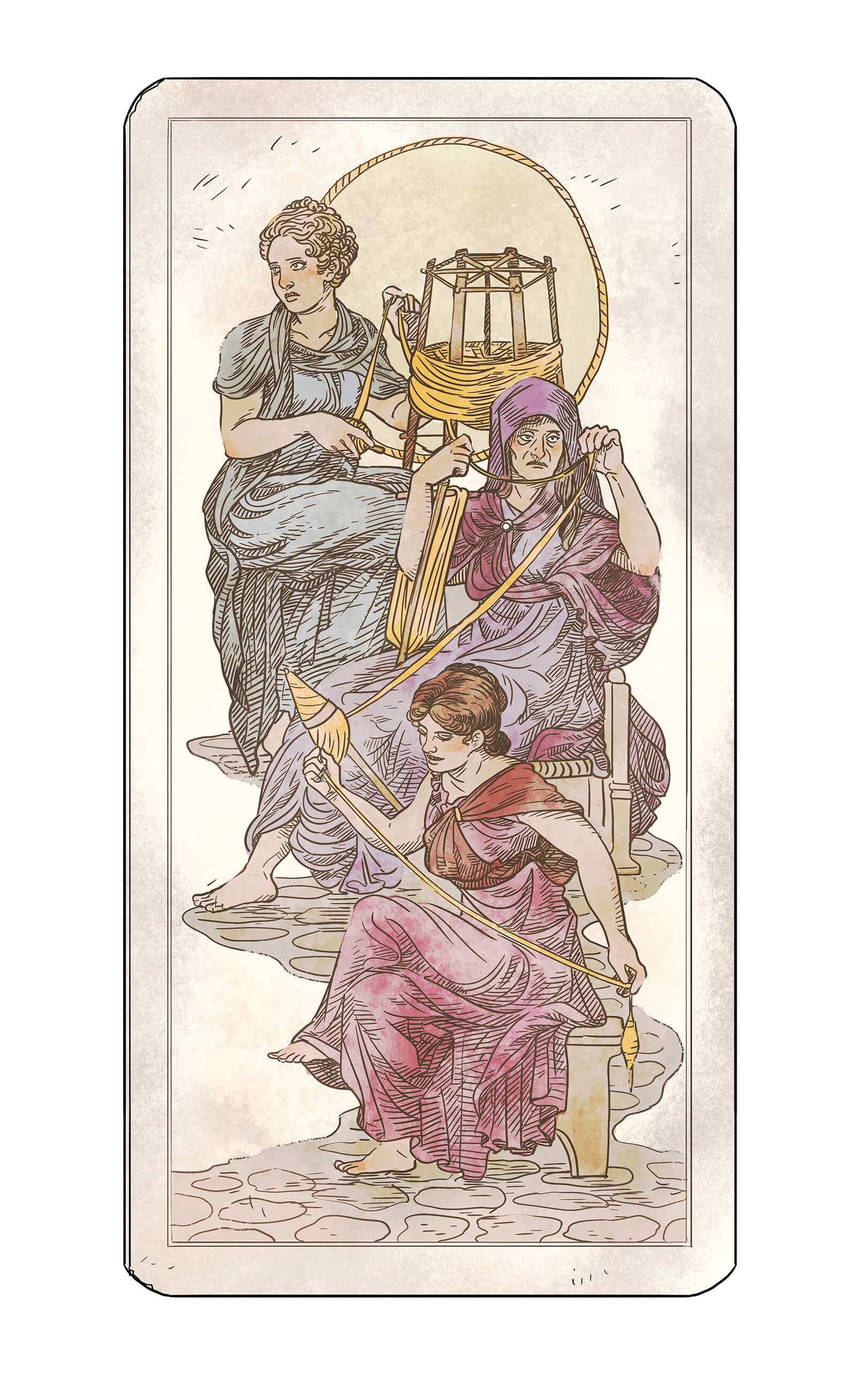

LE TRE PARCHE

You wake from your dream on a cold stone bench in an unfamiliar place. The devil is gone and you are yourself again, but where? Have you walked in your sleep or have whole days lapsed between dreams and reality? Around you, stone walls enclose a grotto littered in dry leaves. Above you, bare branches support a roof of sky.

Three crumbling statues guard the grotto, moss-covered oracles of stone secrets. They could be the three graces — muses of the imagination, or the three fates — weavers of life and death. The statues quiver, shaking dust and grit from their feet as if removing their sandals after a long journey.

The first one turns her head to you. “This place is a portal,” she says. “You came with no purpose but to wander, arriving on the last feast day of San Giacomo.” The second statue holds the eroded remnants of a sword and shield. She speaks in a low voice. “On this day, some souls wake to the light and give themselves up to it. Others remain, trapped between worlds.” The third statue lifts her head. She is so weather-beaten, only the outline of her former shape remains. She has nearly merged with the hollow that held her. “This is your fate,” she says.

You sink to the cold earth floor to rest your head on your knees. “Am I a ghost?” you implore. “Is there nothing I can do?” The third statue speaks softly. “Look to the wall.” Below the fates’ feet, a stone inscription reveals itself. It is worn and rubbed raw, but the words are still legible:

L’antro la fonte e il lieto cielo libero

L’animo d’ogni oscuro pensiero

The cavern spring and the happy sky

Free the mind of every dark thought

As you read, a vision of light creeps through the cracks of your mind. You may be a ghost, but this world is yours to explore — the grasses of the fields and the flowers that grow there, the pages of books and the brushstrokes of paintings. Time is irrelevant; you are free to flaneur. Removed from one world, another opens itself up to you. What is life but the leavings of many deaths?

In the grotto by the garden, if one sits and waits long enough, they may see a wisp or ember waft by on the wind. If it fails to appear, keep watching. It will arrive somewhere — along the garden path or in the candle that beckons from the castle window. Those who feel lonely need only to look up on a clear, dark night. Thousands of souls traverse the sky — through hours, days and centuries — scattered among the stars.